Wiclif Otieno, an Emerging Leader

April 5, 2009

Wiclif at His Home in Kawangware

Wiclif was born in Mathare, a Nairobi slum, and later moved to the upper country to live with his grandmother. He never knew his father and his mother was sick with “the epidemic that strangles Kenya,” HIV/AIDS. Every summer Wiclif came to Mathare to visit his mother and to enjoy the city of Nairobi. One summer, however, he did not have the bus fare to go home to school nor the money to pay the school fees to enroll in a primary school in Nairobi. With his mother sick, he was forced to drop out of school and to turn to the streets to make enough money to support her. He joined a gang of street boys, where he began to smoke marijuana, drink illegal brew and even tried sniffing glue (a habit in which over half of all street kids engage). He hustled for coins, searched for metal scraps that could be sold, worked as a porter, washed cars and even watched cars. Wiclif describes being on the streets as hell. Street kids are shot dead by Kenyan policemen and are thrown into juvenile detention facilities without justification. In Kawangware Kenyan police shot 37 street kids last year. Seven were shot in one day after police asked them to lie down facing the ground and fatally shot each and every one. Wiclif says street kids feel forced to sniff glue as it is “the only shield they have when they search through garbage to look for food and the only blanket they have when they are withstanding cold nights sleeping outside.” While walking around Kibera, the second-largest slum in Sub-Saharan Africa, I saw street boys searching through the rivers of sewage that flow across the slum with their bare hands, hoping to find a coin. The stench alone was ghastly, but the sight of these boys wading through fecal matter to survive was horrifying – a vision of hell on earth.

Wiclif’s main post was at Kenyatta market, where he worked as a porter for “mzungus,” or white people, carrying their produce and products. He had to be weary of the security though, as the security guards would beat the street kids if they were caught in the market perimeter. Wiclif and his friends had no choice but to work there. While working at Kenyatta market, Wiclif met what he calls his “support, benefactor, father-figure and savior.” After tipping Wiclif for carrying his products to his car, this mzungu drove off. The next day, he returned. Wiclif called it destiny and says he is one of the few who have been so lucky, because that mzungu arranged for Wiclif to be taken to a rehabilitation centre, the Light and Power Centre in Kawangware, and sponsored him by paying his board and school fees. After five months Wiclif was rehabilitated and was sent to complete his primary school. Most kids finish at 14, but Wiclif graduated at 18. Before his graduation, both his mother and his grandmother died from AIDS. The other day we drove by Kenyatta market and Wiclif recognized a few of his fellow boys who continue to operate at the market. They were not as lucky as he was.

Wiclif went on to secondary school and graduated when he was 21. Wiclif continued at the Light and Power Centre and learned skills, including bag-making, which he continues to this day. Upon graduation from high school, Wiclif was forced to leave the Light and Power Centre as it was shut down, which Wiclif alleges was due to corruption among management officials. He started volunteering at the Agape Hope Centre and worked with HIV+ women to develop income-generating activities. He became the leader of a support group and trained the women on bag-making and marketing. When Wiclif and I went to meet with the Directors of the Agape Hope Centre, they greeted him with huge hugs and kisses. The Directors call Wiclif their son and an angel and say that most street kids who are provided with opportunities for rehabilitation and re-integration forget where they came from. Although Wiclif’s bag-making business, EcoSafi, is not currently sustainable, I bet it would be if his heart were not so big. He has three employees and all three of them are either drop-outs due to lack of school fees (10,000 Ksh or $120.00 for the school year), are former orphans or are former street kids. Wiclif allows two of them to sleep in his workshop and one of them to sleep in his one-room home. (The four are pictured in the main photo of this blog). Without Wiclif, they would have nothing.

Last year, Wiclif came up with the idea of creating a community program specifically targeting street kids. He contacted his “savior” and proposed the idea of starting a feeding program, which would later be developed into a more comprehensive program promoting entrepreneurship. Wiclif wants to show his remaining colleagues that he hasn’t forgotten them.

Kawangware

March 31, 2009

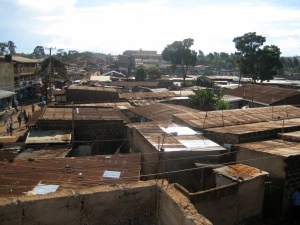

Kawangware

Kawangware

Wiclif suggested we take a matatu, the public “buses,” to Kawangware. The privately owned matatus are decorated to the liking of their owners. Decals of Chris Brown, President Obama, Ludacris and LL Cool J flood Nairobi. After passing an accident scene, we arrived at Kawangware, one of the largest growing slums in Sub-Saharan Africa with a population of at least 200,000. Looking at pictures of slums on the internet, or even watching Slumdog Millionaire did not prepare me. I was in shock. We hopped out of the matatu and walked about 10 minutes towards Wiclif’s house. Although the smell of sewage was pervasive and I had to watch my step as goats and small streams full of trash crisscrossed our path, I could not help but smile. When young kids saw me they screamed “Muzungu! Muzungu!” and ran inside to fetch their parents. By the end of our walk, I had about 9 kids following me shouting, “How are you? How are you?” Wiclif said that “muzungus,” or white people, are seen in Kawangware maybe once a month. I believe him. While Wiclif prepared a small lunch at his home, kids lined up to catch a peek inside.

A Little Boy Watching from Outside

After lunch, Wiclif brought me to his workshop where he and three other boys make custom recycled shopping bags. Wiclif learned how to make the bags while in a rehabilitation centre for street kids in Kawangware. Although originally from Mathare (another Nairobi slum), he was sent to the Light and Power Centre in Kawangware and has since made the slum his home. Although the bag-making business is going slowly as there is fierce competition and a small market, he is able to employ other boys who would otherwise be on the street. Although Wiclif has become somewhat of an entrepreneur, he himself admits that proper training about marketing and business management would be invaluable.

Wiclif's "Boys" in their Workshop (and home to two)

Wiclif and I then walked to his friend Zede’s house. We sat with him to discuss the logistics of working with street kids. It started to pour and the rain against the aluminum roof startled me. Wiclif and Zede did not react. It was so loud and so powerful that I felt as though I were at some sort of alternative techno concert. I couldn’t hear a word they were saying and yet they understood each other perfectly. When the rain let up a little bit, we went to buy some sodas. Little did I know that navigating through Kawangware after rainfall is a daunting task.

Kawangware Post-Rain - A View from Zede's Home

After drinking our Sprite, we said our goodbyes and Wiclif accompanied me to my hotel. Wiclif calls it “serene.”